What Is The Commitment Fee Charged For Handy Monthly Service

Dirty Work

Virtually everything that startups get right—and horribly wrong—happened at habitation-cleaning service Handy.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Didier Robcis/The Image Bank, icons by Thinkstock.

Handy's third birthday party terminal month was everything you'd expect from a startup soiree. Twenty- and thirtysomethings crowded the dimly lit bar at Pergola, a Mediterranean spot in Manhattan'due south Flatiron Commune, munching on skewers of gratuitous-range chicken and a seemingly countless pour of spicy meatballs with tzatziki sauce, as a hoodie-clad co-founder boasted about the company'due south recent triumphs. Handy had good reason to be in high spirits. The startup, whose app allows users to rent, pay, and charge per unit home cleaners, had just completed its one-millionth booking.

I had come up to the political party at the invitation of a Handy PR rep and was making the rounds, introducing myself equally a journalist and chatting with employees. Virtually had drinks in hand and seemed eager to celebrate. Only when I slipped into conversation with a woman from Handy's customer service department, she told me something surprising. "A couple months ago," she said, "we idea the visitor was going to implode." She alluded to outsourcing and infighting, and a workplace culture roiled by anxiety over the company's future.

That didn't track with what Umang Dua, 1 of Handy'south co-founders, had been telling me and another reporter just moments earlier. Since launching in 2012, Handy has expanded to 28 cities, including ones in Canada and England. It employs a full-time staff of more than 160 across all these cities, and has enlisted about 10,000 cleaners to piece of work on its platform. In March, Handy notched $15 million in funding, and is reportedly closing in on some other $50 meg. That could value the company at one-half a billion dollars. The expansion, the millionth booking—all signs point to growth. Sure, Handy isn't assisting even so, but what 3-year-former startup is?

Handy is unquestionably a savvy young visitor, ane that has conjured a valuable new business out of sparse air. But in the weeks following the party at Pergola, I learned that its ascent in the so-called 1099 economic system has been a bumpy one—for its users, its employees, and for the contained contractors who actually do the cleaning.

Former Handy employees I spoke with described a workplace that has conformed to every caricature of the contemporary startup: Grueling hours for staffers. Performance judged on the ground of stultifying metrics. An office culture that is at once elitist and boorish.

As for the cleaners, many have enjoyed the business concern the Handy platform has brought them. Just others have felt exploited by the company's policies. They confront harsh penalties for missed jobs. They must maintain exceptionally high ratings to earn the almost competitive wages and to keep getting gigs. And as contractors, non employees, they enjoy few if whatsoever traditional workplace protections. 3 former cleaners have now filed two carve up suits alleging that Handy classifies them every bit contractors but oversees them like employees—and demanding that the company compensate them for their unpaid fourth dimension and expenses.

Will Handy succeed in condign the Uber of household chores? Or will it come up to serve as a cautionary tale for startups in the white-hot 1099 economy? In that location's no denying investors' enthusiasm for companies that swoop into a sector and establish businesses with lean operations and armies of contractors to do the dingy piece of work. But the imperatives to grow these businesses by leaps and bounds while keeping costs extraordinarily low are pushing companies similar Handy to the brink. Even potential one-half-billion-dollar valuations can't hide the strain.

Every practiced startup has a skilful origin story, ane that begins with a problem and ends with an ingenious, app-powered solution. Uber's founders couldn't get a cab on a snowy nighttime in Paris. Airbnb's execs had extra room in their loft. Handy began with a mess.

It was May 2012, and Oisin Hanrahan, a first-year pupil at Harvard Business School, had two roommates. The first i, Dua, was messy. The 2nd, a guy named Dan, "was really messy." The iii set out to enlist some help getting their home in order, but finding a cleaner in the Boston area was surprisingly hard. At that place was no online booking service. No convenient times available. No reliable, centralized rating system to assess the options. "Nosotros had exactly this trouble," Hanrahan says, "of how practice y'all find someone you can trust to clean?"

Photo analogy by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Izabela Habur/Getty Images.

Handybook, as information technology was initially chosen, launched in Boston that month. Hanrahan and Dua'due south vision was to create a digital platform that would help customers find trustworthy cleaners for their homes, and help good service providers discover work. In June, Handybook pushed out a version for New York Metropolis. That fall, Hanrahan and Dua raised a few 1000000 dollars in capital and before long afterward moved their five-person team to New York. They borrowed their first office from General Catalyst, i of the company's investors. At the time, they had fewer than 100 cleaners using the service.

The operation was lean by design, in line with the gospel of the 1099 economy. The core belief of its evangelists is that you can build empires without actually owning much of annihilation and without actually employing the people who evangelize your services. (The moniker 1099 nods to the tax forms the IRS requires of most contained contractors.) In the 1099 economic system, the company'south role is to facilitate 2 sides of a market place, linking people who accept time and skills to people who need their help.

Home services seemed like a good fit for the 1099 approach. In the past, getting your house tidied typically involved either hiring someone through an expensive cleaning company or searching for assist on the grayness market. Handy made the process as easy equally tapping an icon on a screen. To volume a cleaning through Handy's app (or its website), you type in your ZIP code, the number of rooms in your home, and an ideal appointment and time. Handy spits dorsum a recommended cleaning duration, a cost quote, and a list of available slots. In New York, for example, a three-hr cleaning will run yous around $80, though piece of cake-to-obtain coupon codes can bring the price far lower. (The company also offers other "handyman" services like furniture assembly and moving assist, but cleaning makes up the majority of its acquirement, at 85 percentage every bit of concluding fall.) Handy says it earns about 20 percent on the average booking, a effigy in line with, say, what Uber typically takes for rides on its UberX platform. "Handy's fully vetted professionals provide top-quality dwelling house cleaning services," the site promises. "Put down the sponge and permit Handy'southward cleaners take care of the dirty work!"

Handy'south idea landed right when tech-industry investors were in a fervor for companies that provided on-need conveniences and gig-based innovation. The company scooped up $10 million in funding in October 2013, and by the end of the year it was alive in 12 cities. In spring 2014, a few months later on receiving a $iii.7 1000000 infusion, Handy launched in a dozen more than cities, including its offset international one, Toronto. Another $30 1000000 of financing followed that June, and a calendar month later Handy headed to London. The company was growing exponentially—and its customer base was growing with information technology. In March 2013, Handy booked 1 appointment every ninety minutes. One yr later on, it was booking a client every three minutes. Past September 2014, it was 1 every 30 seconds.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by Anna Peisl/Stone/Getty Images

To accommodate this ferocious expansion, Handy went on a hiring spree. The team of actual employees at Handy headquarters, which in February 2013 was nonetheless only v people, grew to fifty over the next 12 months. Handy had a pocket-sized corps of programmers and other staffers who kept its digital platform ticking, simply a big number of new hires were concentrated in the client experience squad, the group tasked with fielding questions, complaints, and other inquiries from both Handy'south customers and its cleaners. In spring 2014, Handy began onboarding customer-experience employees in "classes" of seven to 10 people at a time. Quarters grew tight rapidly, and the company bounced around Manhattan from part to function. It was a classic startup atmosphere: Erstwhile employees draw fast-paced and demanding work powered by catered meals, aplenty snacks, and a well-stocked alcohol closet. (Snack orders included numerous 30-racks of Bud Light.)

This past November, at the annual Web Summit in Dublin, Hanrahan explained why the company had pursued such aggressive growth. It was "scale for the sake of a improve customer experience," he said, a strategic push to solve bug of supply and demand. More cleaners in each city meant shorter wait times and greater flexibility for customers. At the same time, more customers meant greater chore availability for cleaners. Managed properly, growth in supply and demand would become self-sustaining. "I call up calibration for the sake of scale is stupid," said Hanrahan, who serves as Handy's CEO. But scale for customer experience, "like, that makes a shitload of sense."

Nevertheless as Handy scaled, its in-business firm functioning was experiencing growing pains. In reporting this story, I spoke or emailed with 10 old and two electric current Handy employees, four of whom were put in bear upon with me by Handy. Of the former employees, ix left on their ain terms and one was fired. Ii now piece of work for some other cleaning startup. With the exceptions of Justin Martin, who was the lead of Handy's engineering science team from October 2013 to March 2015, too as the four people Handy connected me with, the sources requested anonymity because they feared retribution from the company and, in some cases, had signed nondisclosure agreements. The anonymous former employees recount operational problems and a direction squad they saw as out of touch with bug on the ground. They also draw a visitor whose culture was abrasive, often inappropriate, a "Harvard boys' order," and, in its early days, sexist. They detail a scaling process in which employees struggled to keep upwardly with the visitor'due south rapidly expanding offerings, leading an already frat-similar civilisation to curdle into something worse. I asked each of the erstwhile employees what they liked virtually Handy. The cheeriest response I heard was, "it was definitely a learning experience."

Many startups, born in business concern schools and forced to grow up fast, run into a tough reality similar this sooner or afterward. But Handy, hurtling toward success, crashed into it hard.

Handy is reluctant to acknowledge these bug, much less discuss them. "Handy has apace expanded, and task duties for some individuals changed over time. As we experienced this growth, nosotros were proactive in evaluating policies and establishing best practices for our business organization," a company spokesperson writes in an email, when I ask what the company has done well and what it could have washed ameliorate. "Through this process, we have become a better, stronger company."

The employees I talked to said that process wasn't always a smooth one. The first signs of trouble emerged in summer 2013, as Handy'due south expansion ramped up, and the company's nonetheless-small staff had to residue recruiting users, onboarding cleaners, fixing technological bugs, and resolving customer issues. The strain fell particularly hard on the fledgling customer-feel team. Its 5 members routinely worked 12-hour days, five or six days a week. Withal, await times on Handy's customer service phone line would often top an hour or two.

"Customers were merely yelling at people because the arrangement was actually bad, cleaners were not showing upwardly, stuff like that," says an early member of the client-feel team. He and another employee who was there that summer say Dua would often sit listening to the client-feel team field complaints and "scream" for cleaners to be fired. "A lot of [early Handy employees] broke downward crying all the time," one says. "It was merely a horrible place to be." A spokesman for Handy says the story about Dua is "totally false."

The autumn of 2013 constitute Handy still struggling to fix its customer-experience bug, likewise as develop applied science fast enough to accommodate its surging growth. The visitor "experienced periods of loftier demand where call await times were longer than desirable," Handy'south spokesman says. The pressure to improve "was noticeable by the culture of the company," says Martin, who left this March to beginning a new visitor. "We were growing really quickly and nosotros were only racing to build the technology to help deal with this." Today, Handy says its boilerplate telephone call expect is between 2 and three minutes.

Former Handy employees draw an office that, early on in the company'due south existence, tolerated joking vulgarities like a "Wheel of Fellatio" (a makeshift Wheel of Fortune with sex acts instead of dollar amounts) and team members who oftentimes referred to female employees every bit sluts. "Just like, 'Oh, y'all're a slut,' " says one of Handy'south early customer-experience employees. "I don't even know why that happened." In the summer of 2013, a whiteboard wall in the visitor's office at 350 Seventh Avenue in Manhattan would oftentimes display crude and offensive language. One week, a missive on the whiteboard managed to fit slurs toward women, blackness people, and gay people into just five words. When one of Handy's neighbors dropped by to inquire that information technology exist taken down, someone used the whiteboard to taunt that visitor. Only later on an employee of the neighboring company emailed Dua did he promise to deal with the messages. Handy says the person responsible for these messages was "reprimanded," "given a written alert," and "no longer works at Handy and is non representative of our culture or our values."

By many accounts, Handy grew out of its worst tendencies, but continued to push the boundaries of appropriateness with frequent alcohol consumption and a visible hookup culture. "Lots of gossip among senior leadership about who'due south hooking up with whom, photos being shared," says a sometime operations employee, who left this spring. "Our cultures were very much fueled past alcohol."

Handy broadly contests how former employees characterize its piece of work environment. "We have our culture extremely seriously and are committed to building an inclusive, supportive organization," Handy's spokesman writes, when asked whether company culture has ever been inappropriate or abrasive. Asked about a "hookup" civilization, or ane driven by booze, he responds, "That characterization is totally off base." Handy is "proud of the fact that we bring people together in an environment where people relish doing meaningful work and in the process form real friendships," the spokesman writes. When I inquire about the Cycle of Fellatio, the spokesman tells me this is "the beginning we've heard of a 'bike,' " calculation, "that sort of thing has no place at Handy." (The 2 former employees who described the wheel also provided Slate with a photograph of it.)

In the summer of 2014, Handy hired Carrie Zuchorski, a old executive at Weight Watchers, every bit vice president of customer experience. With her arrival, five former customer-feel employees say the already overwhelmed department became fifty-fifty more so thanks to the imposition of rigid, metrics-focused goals. Employees were required to have a sure number of "customer interactions"—things like emails and phone calls—every 60 minutes. They were publicly ranked and given preference for picking shifts based on the quantity and quality of their service. Former client-experience employees say they were also hamstrung past poor communication between departments. When the product squad made changes to Handy'due south app, two sometime employees say, the customer-feel team would sometimes simply larn about it when confused users chosen in. On top of that, customer-experience employees were at present being monitored on everything from when they arrived to how long they spent eating lunch and taking bathroom breaks. Morale plummeted. "It definitely started a culture of resentment," a one-time associate in the department says.

What struck these former customer-experience employees as callous policies were to Handy'south mind necessary for running the growing business. After Zuchorski'due south arrival, the visitor had switched its customer-feel squad from salaried to hourly positions. "Keeping track of get-go and end times are important to make sure our employees are properly compensated," Handy'due south spokesman says in a statement. "Additionally, breaks and when agents are away from their desks are monitored to provide customers with the best experience possible. If a [customer-feel] employee is not at their call station, that needs to be recognized in the system" or else "calls will continue to be routed to them when they are not available to answer them."

Fifty-fifty with these changes in place, by the autumn it became clear to Handy that the Manhattan-based team wasn't working out. Employees there tended to want more than career evolution than Handy could beget, and the resources dedicated to them were detracting from other parts of the business, similar "growth or marketing role," Hanrahan says. "Information technology just wasn't a skilful fit." The platform also needed to support hundreds of thousands of customers, thousands of cleaners, and call volumes that could run every bit high as ten,000 in a week. So Handy started outsourcing customer-experience positions to call centers in Missouri and Florida ("a more than mature and sophisticated customer service team," the spokesman writes). But instead of shortening phone queues and easing workloads for people in New York, outsourcing made things worse for the in-firm client-experience members who remained. The call heart employees were unfamiliar with Handy'southward systems, their former New York counterparts say. Stress climbed. Wait times, which had improved to around 15 minutes, increased once again. Over the adjacent few months, several customer-experience employees quit.

Early this twelvemonth, Handy began to burn down people in the customer-experience department. "They would fire them like 10 at a time," says a former employee, who quit this March. "They didn't do it in front of us simply all the briefing rooms were glass. So they would call people in and then you would come across people gather their stuff and leave." In Handy'south New York office, the customer-experience team that once numbered around 100 employees has dwindled to well-nigh ii dozen.

Equally intense scaling took its cost on the company's culture through the first half of 2014, it also wore on Handy's financials. Transforming the market for home services in 28 cities isn't just aggressive—information technology's expensive. Onboarding each new cleaner in the U.S. toll hundreds of dollars, 2 employees who were involved with operations say: Expenses included background checks, phone interviews, and a $250 initial cleaning kit whose cost was partially borne by the contractors. As of this Feb, Handy was bringing on 400 to 500 new cleaners in a unmarried week, i of those employees estimates. Handy, which says it all the same brings on hundreds of cleaners each calendar week, sets the electric current onboarding price significantly lower, at less than $100. Even then, that'southward plenty to easily bring Handy's spending on enrolling new cleaning "pros"—equally it refers to contractors—to tens of thousands of dollars each week.

Investing a lot of coin to vet cleaners didn't do much to ensure that they'd stick around, notwithstanding. Co-ordinate to i of the employees who worked in operations, Handy's internal metrics showed that within 60 to 90 days, between xx and forty percent of new cleaners would become inactive on the service. (Handy prefers the inverse framing, noting that the majority of pros are still active subsequently iii months.)

To most of the one-time customer-experience and operations employees I spoke with, that loftier turnover was hardly surprising. At various stretches in the visitor'south beingness, contractors ofttimes encountered problems receiving payments, old customer-experience employees say. Lots of cleaners also didn't sympathize that, because they were independent contractors, in that location was no withholding on their earnings, and they needed to set aside coin to pay taxes.

But the most glaring payment complaints involved Handy's pay-docking policies. Cleaners would take money withheld from time to come paychecks if they showed up late to a task, canceled on short observe, or missed an appointment entirely. These financial penalties are outlined in the "Service Professional person Agreement" that all Handy service providers are required to sign. "Cancellation past Service Professional may result in a fee being charged to Service Professional as described further in Schedule 3, which may exist modified from fourth dimension to time by Handy," the terms read. So may "Service Professional's failure to consummate a Job in accordance with Service Requester'due south specifications." Cleaners who receive poor reviews from customers also earn less per hour and risk removal from Handy's service—a fact largely invisible to users of the service.

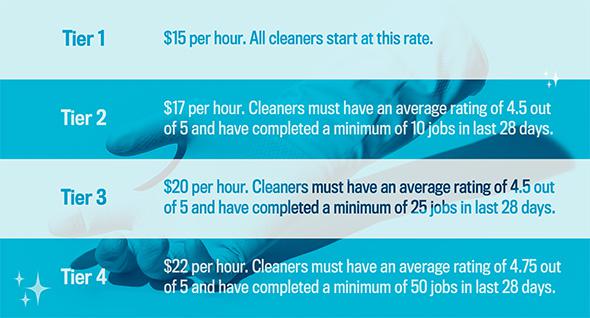

Handy cleaners are paid one of four hourly rates between $15 and $22 based on how highly rated they are and how many jobs they've worked in the past 28 days. The average cleaner makes around $17 an hour, Handy says. Per the company policy viewable to pros on the Handy app, which a former employee provided Slate , Handy withholds $15 from the pay of cleaners who arrive belatedly to a job past more than than 30 minutes, as well as from those who cancel a booking less than 36 hours before the start fourth dimension. Cleaners who don't testify up at all are assessed a $35 penalty (plus the cost of the task, if the payment has already processed). Nigh severe is the fine for cleaners who abolish jobs within two hours, who incur a withholding fee "equal to what you would have been paid if you completed the job." In other words, pull out of a $threescore cleaning task at the last minute, and you lot don't just lose the $60 earning opportunity—you're actually charged $60.

Chart by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photo by John Spannos/Thinkstock.

Handy says these policies mirror how information technology charges customers who cancel bookings. "It's a dual-sided understanding where we want to deliver the best feel to customers and pros," Hanrahan says. "If the customer cancels a booking inside two hours, nosotros actually pass the unabridged fee onto the pro, and so the pro gets paid the entire amount irrespective of what happened." Fees assessed to cleaners are typically used to give customers credits for complimentary services.

Still, the policies troubled many members of the customer-feel team. "Obviously if they called in and were like someone died, 'my car broke down,' real reasons, nosotros would reverse it," ane former employee says. "But I would always worry about people who weren't going to telephone call in because they were worried well-nigh losing their jobs," she says, noting that Handy'southward cleaners in New York are predominantly lower-income blackness and Latino women. "It was a really unfair system, and I felt so fucking guilty all the time, because I knew that the system was broken and that I couldn't do annihilation about it."

The cleaners I spoke with are torn between warm feelings for a platform that affords them flexibility and relatively good earnings and a frustration that Handy treats them similar disposable contractors despite managing them quite closely. When I tried Handy earlier this month, information technology went well. The woman who cleaned my apartment was prompt, friendly, and polite. Shortly after arriving she changed into a baggy Handy shirt with a slight shrug, then set to work scraping the grime from my bathroom. She said she'd worked in cleaning for a long fourth dimension and that using Handy made it easier for her to notice jobs. I heard similar things from Sewanda Williams, a cleaner who has worked for Handy in San Francisco for a little more than a year and likes that she can schedule cleanings in the evening, effectually her 9-to-5 chore.

But Williams' experience has not been without its frustrations. She has been irked when Handy has made small changes to its payment rules "without really contacting you or giving you warning." Another woman I spoke with, who has cleaned for Handy in New York for almost 3 years and requested anonymity since she still works on the platform, complains that Handy tells customers that they are "non expected" to get out tips. She describes recently not receiving payment for a job in a timely mode because of identity verification issues, but says that rather than assist her over the phone, Handy would only communicate with her via electronic mail. "I think it'due south actually unprofessional," she says.

The cleaners I talked with know Handy isn't perfect, but they have decided to take the problems—the lack of tips, the poor cleaner support and questionable treatment equally contained contractors—in stride. "I dear Handybook," the New York cleaner insists. "They are a expert company, it's just fiddling issues they've got."

Not every Handy contractor is then forgiving. Terminal October, two former cleaners filed a class action lawsuit confronting Handy in California, claiming a litany of labor violations. The adapt, brought by the sisters Vilma and Greta Zenelaj, alleges that Handy failed to compensate them for their total time, including travel; failed to pay a minimum wage for all hours worked; failed to provide residual and repast breaks; failed to reimburse for business expenses; failed to remit tips; and failed to furnish timely wage statements. Uniting all of these was a central assertion: "Handy violates California law by misclassifying Cleaners as independent contractors when they are, in fact, employees." Ii weeks agone, another class action lawsuit was filed against Handy in U.South. District Court in Massachusetts alleging much the same.

Handy is far from alone in the 1099 economic system in facing legal obstacles. Over the past few years, contractors have filed like suits against Uber, Lyft, laundry service Washio, food delivery services Postmates and Caviar, shipping platform Shyp, and Handy competitor Homejoy. Representing the plaintiffs in many of these cases is Shannon Liss-Riordan, a Boston-based attorney.

Screenshots via Handy app.

The Zenelaj complaint argues across thirty pages that Handy was exercising "all-encompassing control" over how cleaners performed their jobs. Information technology was, in other words, treating them like employees, but paying them similar contractors. Handy required cleaners to nourish training sessions, gave them an "all-encompassing Handy-labeled checklist" to follow, instructed them on what supplies to use and how to dress, detailed how to interact with customers, and monitored performance. It too could terminate cleaners at its discretion. I onetime Handy cleaner I spoke with said she was required to attend a two-hour, unpaid preparation session at a Handy employee's flat before being hired to work on the platform. In presentations Handy used at cleaner grooming and orientation equally late as fall 2014 (copies of which were provided to Slate by a former employee as well equally by Liss-Riordan), the company outlined its intricate rules and strict expectations. Cleaners were instructed to follow Handy's five "gilded rules": showing up to jobs, bringing supplies and wearing Handy apparel, existence on fourth dimension, beingness thorough, and being professional. "Breaking any of the Golden Rules can lead to removal from the Handybook platform," the presentation cautioned.

Such quality controls are necessary for any business, but especially i like Handy, which wants to tame the rangy market for dwelling house services. "This is not an easy business," Hanrahan says. "You want to strike this balance betwixt incentivizing great behavior and incentivizing them to do a dandy job. And, at the aforementioned time, in the event that they can't do a peachy job, you want to give them the opportunity and feedback on how they can exercise better. But if they're not delivering a client feel that's in line with what your customers want, yous need to suspend them from the platform."

To a judge, though, "incentivizes bang-up behavior" might tiptoe too shut to "exerts control like an employer." Information technology'south a line many 1099 startups have struggled to walk. Uber, for example, doesn't make its drivers clothing uniforms, but does advise them on how to collaborate with customers and threatens to deactivate those who fall beneath sure ratings thresholds. Is that plenty to brand Uber the employer of its drivers? A jury volition soon weigh that question. Other companies, like Shyp and grocery-service Instacart, have decided to play information technology condom and switch some or all of their contractors over to employee condition. At the same fourth dimension, companies save an estimated thirty percent on labor costs from working with contractors instead of employees, says Wally Hopp, professor of technology and operations at the University of Michigan's Ross Schoolhouse of Business. They have a powerful incentive to keep their workers off of their staffs.

In Handy's case, a ruling that its cleaners are actually employees might also open up the company up to other legal problems. Sarah Leberstein, an chaser at the National Employment Law Project, says that Handy's detailed and punitive withholding procedures would likely be illegal if they were applied to employees in New York, since the country department of labor's list of permissible deductions includes health benefits, charitable contributions, kid care, and various other payments "for the benefit of the employee," but not belatedly fees. It'south policies like these, combined with Handy's comprehensive cleaner trainings, its strict scheduling, and its control over cleaner pay rates, that advise to critics like Liss-Riordan that the company has stretched the boundaries between employees and contractors more than many other startups in the 1099 space. "Handy is one of those companies that I believe is crossing the line in even more blatant ways," Liss-Riordan says.

In a victory nevertheless perhaps besides a bad omen for Handy, the visitor's main U.S. competitor, Homejoy, appear concluding Friday that it would shut down at the end of July. The "deciding factor" was four lawsuits filed confronting the company, Homejoy co-founder Adora Cheung told Re/code. Homejoy's exit leaves Handy the ascendant abode-cleaning platform in North America. It has won the market. "Handy carefully built out a city-by-city strategy," says Jeremiah Daly, a former Handy investor. "The business concern had a competitor that was expanding what appeared to be quicker, only the manner these markets are won, it's unclear whether information technology's the biggest company by revenue, or the nigh fundamentally sound visitor that wins at the end of the twenty-four hour period." But Handy still faces legal questions similar to the ones that caused Homejoy to go out the market.

Could Handy go the style of Homejoy? Might information technology have to concede, equally Instacart has, that the contractor model at the centre of the 1099 economy threatens the soundness of its business? The visitor seems to be asking itself these questions, considering it's already making changes.

The problems Handy ignored as information technology careened toward success may have seemed peripheral at the time, just they've ultimately proven much more complicated, and arguably more of import, than any questions of supply and demand. Handy figured out how to tidy other people'due south homes, but along the mode information technology neglected its ain household. With unhappy cleaners seeking relief in the courts, Handy'southward contested labor model may before long face up a reckoning, and perhaps be in need of revision. That's a mess this dynamic visitor may yet find a manner to make clean up. But for once, it'south going to take to do the dingy work itself.

Handy is also hoping that a growing debate among economists, politicians, and lawyers over the old classifications of "employee" and "independent contractor" could lead to the cosmos of a new, third employment category. One much-discussed idea is the "dependent contractor," who would enjoy certain labor protections traditionally afforded to employees—perhaps a minimum wage—but retain the scheduling flexibility of a contractor. "We know we can't turn back the clock on the new economy and we can't turn our back on the independent professionals who work then hard to evangelize high-quality services to consumers," a Handy spokesman writes in an email. "At Handy, we recognize that this means that there may need to exist new rules of the road. That's why we remember information technology's time for an open up dialogue betwixt companies, workers, consumers, and regime about how to foster the new economy in a way that protects workers and ensures that the sharing economy continues to create jobs and spur innovation."

Courts, regulators, and legislators may solve that problem in the coming years, but improving company civilisation is a thornier affair. "I think Handy had a challenge or two scaling culture (although they are doing a better job today)," Regan Bozman, Handy's former master of staff, wrote me in an email. "Onboarding 20-plus employees per month and integrating them is really challenging. However, by nearly March 2015 there was a real recognition that this was an effect, and I think Umang and Oisin did a skillful job of addressing information technology." Shortly before Christmas—as customer-experience employees were quitting, but before they were beingness fired—Handy implemented a "culture committee" to plan events like happy hours and yoga sessions.

Two current employees that Handy's spokesman put me in touch with offered brochure-ready statements about their experiences. "I enjoy the infectious passion Handy team members accept for the success of the company. We're all in it together," Krista Karjalainen, who handles engineering outreach for Handy, wrote in an email. (She besides accidentally forwarded me an exchange with a company spokesman, which revealed edits and additions he had made to her answers to my questions.) "I can definitely say Handy has a great squad with very smart people," Mayank Yadav, Handy's product director for growth, said in his email. Both said they never felt that Handy's civilisation was sexist or elitist.

When I met Hanrahan recently in Handy'south office, even so, I got a more measured response. He seemed taken aback when I began to share the stories I'd heard from former employees, describing the kinds of problems that aren't hands remedied past visitor birthday parties or countless snack supplies. "I call up that any business organization starting out has a vision for what y'all want the company culture to be like, how you want it to feel," Hanrahan said with what struck me as 18-carat artlessness and a hint of regret. "I think people tin always do better in terms of culture. I recall y'all look at something you congenital and you lot always feel like, 'Hey, how can I make this better?' "

Handy could benefit from more of that introspection. But soul-searching isn't easy when y'all're racing to dominate a market place—to put up large numbers, to raise huge sums, to become a household name—all before someone else beats you to information technology. For three years, Hanrahan, Dua, and their team accept trained their focus on that goal. They've summoned their empire out of nothing. They've booked its services a one thousand thousand times over. They've watched their main competitor step aside. By the metrics solitary, Handy is winning, but victory is about more than than numbers, even in the 1099 economy.

Source: https://slate.com/business/2015/07/handy-a-hot-startup-for-home-cleaning-has-a-big-mess-of-its-own.html

Posted by: smithwhane1992.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Commitment Fee Charged For Handy Monthly Service"

Post a Comment